It was great to get some responses and ideas from you after my first blog – thank you! So to explore a bit more, I think that it will help (me at least) to break ‘the Art of Enough’ down a little, to think about:

- The Art of Enough for Individuals – what are the challenges for us in finding ‘the Art of Enough’? How can we develop and share personal stories and practice to help find this?

- The Art of Enough for Organisations: how do businesses and organisations respond to creating a culture where ‘enough’ is a viable and credible options for all employees – including senior executives

- The Art of Enough for Society: how do our personal choices and working cultures impact on the bigger challenges facing our societies? Can the aggregate of individual choices really make the difference that is needed to our environment?

So starting with individuals – for the last fortnight, I’ve been thinking about how the rise in complexity in our lives has impacted on how we live and work – especially in relation to the digital demands on us.

The world is increasingly complex. On pretty much every measure, in every context, complexity is on the up. Take the PEST analysis – it’s a well-used tool in business, analysing the impact of Political, Economic, Social and Technological factors on a particular business – in every one of these areas, the analysis always comes back – there is more complexity than ever before. This is, in part, because we are digitally connected in a global world. So we are no longer just looking at, or operating in, or talking to people or connecting with the things that are happening in our local space. We’re inter-dependent. It’s global. Our frame of reference has changed, along with the speed with which we access it.

The opportunity provided by digital capability is undoubtedly a good thing. Connectivity provides huge potential for communication, connectedness and networking. I love that I can skype my friend in the US or play online chess with my friend in Australia. But there is a darker side. There is plenty of evidence demonstrating how distractible our 24/7 digital world has made us, and the strains of that. On average we check our devices 200 times a day. That’s once every five minutes. Since 2010 there is a newly identified form of clinical anxiety called ‘nomophobia’ – literally abbreviated from ‘no mobile phone phobia’ – that’s clinical anxiety created by not being connected or able to access a digital device. I was once coaching a very senior global leader who described a physical panic attack that she had when she went on holiday to Costa Rica and found that she could not get internet coverage on her phone. She was unable to check her work email for 4 days and she described this as ‘ruining her holiday’.

We are under pressure to be available, responsive, immediate. Even though we know it is not always productive to be so distractible. Linda Stone (former Microsoft executive) coined the term ‘continual partial attention’ – which expresses what happens when we try to be connected all the time. She suggests that in this state we are giving a mere 45% of our attention to what we are actually doing in the moment – so in conversations, tasks, time in meetings, time on the phone, time at home – we are constantly semi-present or you could say, semi-absent – we risk never giving anything our full attention. Which is stressful. There are too many demands on our time – and it can seem as if we can never really do enough.

When we can work anywhere and anytime, access anything, communicate with anyone, then what happens to our boundaries? And how do we manage complexity without it causing our brains to meltdown?

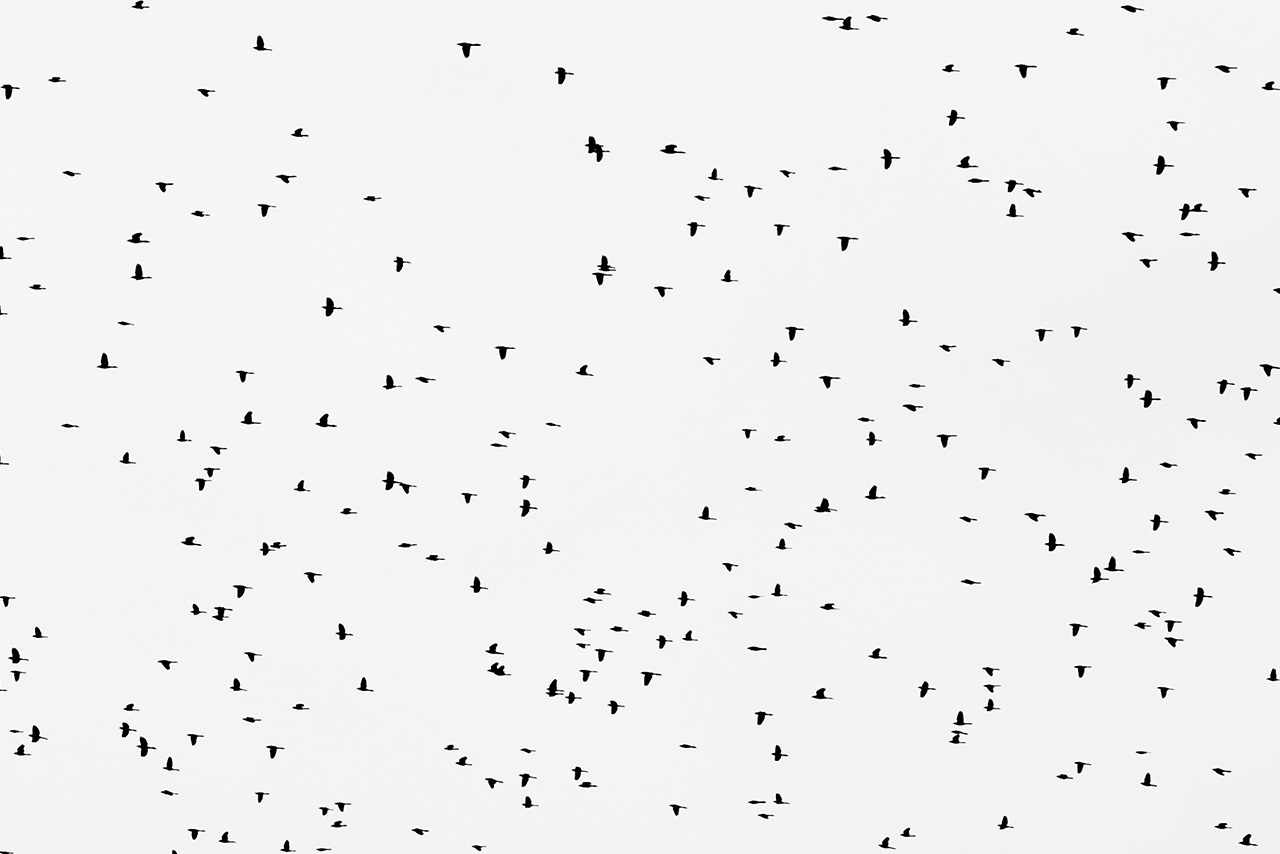

A few years ago, I read and was very taken by a great book called, ‘Weaving Complexity and Business; Engaging the Soul at Work’ by Roger Lewin and Birute Regine. In it they introduced me to what are known as complex adaptive systems – nature’s way of accommodating complexity by creating systems that self-organise and can respond to the multiple and varying changes. They do this in a way that is constantly generative and creative – and at the same time maintains an emergent order. One of the examples they give of this is a flock of birds – for example a murmuration of starlings (my favourite collective noun). I was so taken by this concept that I became fixated on seeing these birds in action. YouTube has loads of amazing footage (which I highly recommend) but I wanted to see them for myself.

So one Sunday afternoon in winter, I cajoled my partner and our then seven and five-year-old daughters into the car and we drove off in search of the RSPB marsh nearby where I was promising them the sight of their lives. After two hours of driving around a lot of bleak looking moorland with no luck, we gave up. On the way home my five-year-old, determined to cheer me up (I was in a ‘what a waste of time’ funk), pointed out a couple of blackbirds flying dolefully across the winter sky.

“There are some birds Mummy!”

“That’s NOT THEM!” was my terse reply. But in so many ways, she was of course teaching me something about the Art of Enough!

(We have, I’m glad to say, since seen a murmuration of starlings, quite by accident on holiday in Northumberland. Fantastic. But I still recommend the YouTube footage for those who feel less driven to see them live.)

So, what can these murmurations tell us about complexity – and the Art of Enough? Well, it is staggering to understand how tens, sometimes hundreds of thousands of birds manage to flock in apparently co-ordinated, often beautifully choreographed sequence? It’s astonishing. What are the rules that allow them to do this? How can we mimic this so that we too could be creative, self-organising and autonomous all within a coherent complex system?

Research shows that these little birds really are just following three rules (called by complexity theorists ‘defining principles’)

For a murmuration of starlings it’s:

- Fly at the same speed as the other birds

- Follow another bird

- Don’t crash.

Yes, really. Just those three. Researchers into complex systems spent years programming a replica system for a computer, (called ‘boids’ – you see what they did there!) and this is the only algorithm they needed.

So, I wondered, is there something we could we use in this simplicity within complexity to help unlock ‘art of enough’? I started to think about what three defining principles would work for me. Three rules that would allow me to be responsive, adaptive and creative within complexity rather than be overwhelmed by it.

Just because I love the collective noun, I’m going to call them my ‘murmuration three’, and here are some that I’ve been trying lately.

- Manage my own digital boundaries.

Checking my phone for emails or messages has become a habit. I do it when I don’t need to, spurred on by a combination of FOMO (fear of missing out) or worse, fear of missing something urgent or if I’m honest, just for a distraction. I was in the habit of checking it in the morning when I first woke up, and at night before I went to bed. If I received a work email at 5 in the morning and I was already awake, I would respond. Ditto for 11 at night. When this happened, it affected my sleep. So I decided to stop and set my own boundaries. No-one else was going to tell me not to send an email at midnight.

For the last few months I do not keep my mobile phone in my bedroom overnight. And I don’t send or read emails during what I have identified as ‘family time’ – and for me that includes not checking my phone. It helps that I’ve stopped my phone from notifying me every time I get an email too, so I don’t experience that sense of urgency of response.

I also turn off my wifi when I’m trying to write or need to concentrate – so that I simply can’t check the bbc website as a pointless distraction! Very much work in progress, but it helps.

- Cut distractions – be fully present in the situation I’m in.

This includes turning off my phone when I’m with other people. I recently read some research which found that even putting a phone face down on a table in a meeting, diminishes the belief of others in the room that they are being listened to. It sits there as a potential distraction.

I’m also trying to focus on each task I’m trying to complete without interruption, rather than get overwhelmed by everything. Breaking things down into small chunks helps me with this. As the old adage goes, ‘you eat an elephant one mouthful at a time!’ (Yuk!)

Perspective is everything of course, and I find it hard to remember sometimes. For me the Art of Enough here is as simple as saying at times when it all gets too much, “I can only do what I can do” and learn to live within the implications of that. (“There are some birds Mummy!”)

Being present for me also means trying to be aware of the distractions in my head, and learning how to turn the volume of these down.

- Grounding myself at the start of each day.

I’ll use a sporting analogy here. I play squash – and as any squash player will tell you, in order to win, you want to stand on the ‘T’ in the middle of the court and not chase the ball around. I liken this to the complexity of the modern world. If I ‘chase’ the complex demands, I will end up running around and achieving little. Mindfulness, exercise, writing – all these daily disciplines (if and when I manage to do them daily) help to keep me centred. And I hope to explore the implication of each of these practices more in future blogs too.

Like real complex adaptive systems in nature, my ‘mumuration three’ rules might change over time – I will need to adapt to the complexity around me. But these are three that at the moment seem to be helping me as I explore my own personal Art of Enough. By being able to navigate complexity, I find myself not being swamped by it.

So those were this fortnight’s musings. Please carry on telling me your thoughts and experience. I’d love to hear from you – especially any ‘murmuration three’ rules that you are finding help you navigate the complexity that we inhabit. Next week I’m reading about behavioural economics. I’ll let you know how I get on!